by Alexis Allison, Fort Worth Report

September 21, 2021

The woman in the third car outside of Las Vegas Trail Rise food pantry wanted to talk. It was about 9 a.m. on a Tuesday, and she was waiting in a food line that wouldn’t start moving for another hour.

She’s lost people to cancer and COVID-19 as recently as last weekend, she told Carlene King, the community health worker standing outside her driver’s side window. The woman wept, and King took her number.

She said she would call her later and refer her to Cancer Care Services, the nonprofit that employs King as a liaison between the community and the company: “This is why I do what I do.”

The interaction took three minutes, maybe four, a moment of intimacy amid rolled-up windows and language barriers and people who didn’t want to chat about cancer while they waited for food.

A similar moment occurred two days before at a church across town. Fatu Holloway, a community health worker at Tarrant County Public Health, was giving a presentation for Birdville ISD about the county’s Women, Infants and Children program, which provides nutritional services to pregnant women, new moms and their children. A woman and her pregnant teenage daughter listened nearby, Holloway remembers.

The woman looked “lost,” she said. Afterward, they spoke. Holloway told her where to find baby things like diapers and car seats for free. The next day, the woman texted Holloway: She’d made an appointment for a car seat and wanted to let her know.

“I’m convinced that the (community health worker) role is the answer to every ill out there.”

– Lisa Padilla, board president of the Dallas Fort Worth Community Health Worker Association

A community health worker like King or Holloway may be the hand that pulls a person into a health care system for the first time. A certified, frontline worker who’s usually part of the community in which they work, they serve as liaisons, advocates, educators and, sometimes, someone in whom to confide. “We’re just that friendly bunch,” King said.

And, when it comes to the people most likely to experience poor health outcomes, community health workers may be key in helping reduce disparities.

“I’m convinced that the (community health worker) role is the answer to every ill out there,” Lisa Padilla, the board president of the Dallas Fort Worth Community Health Worker Association, said in a webinar hosted by Cancer Care Services last week.

The rise of community health workers

Community health workers have formally participated in health systems across the U.S. since at least the 1950s, according to the American Public Health Association.

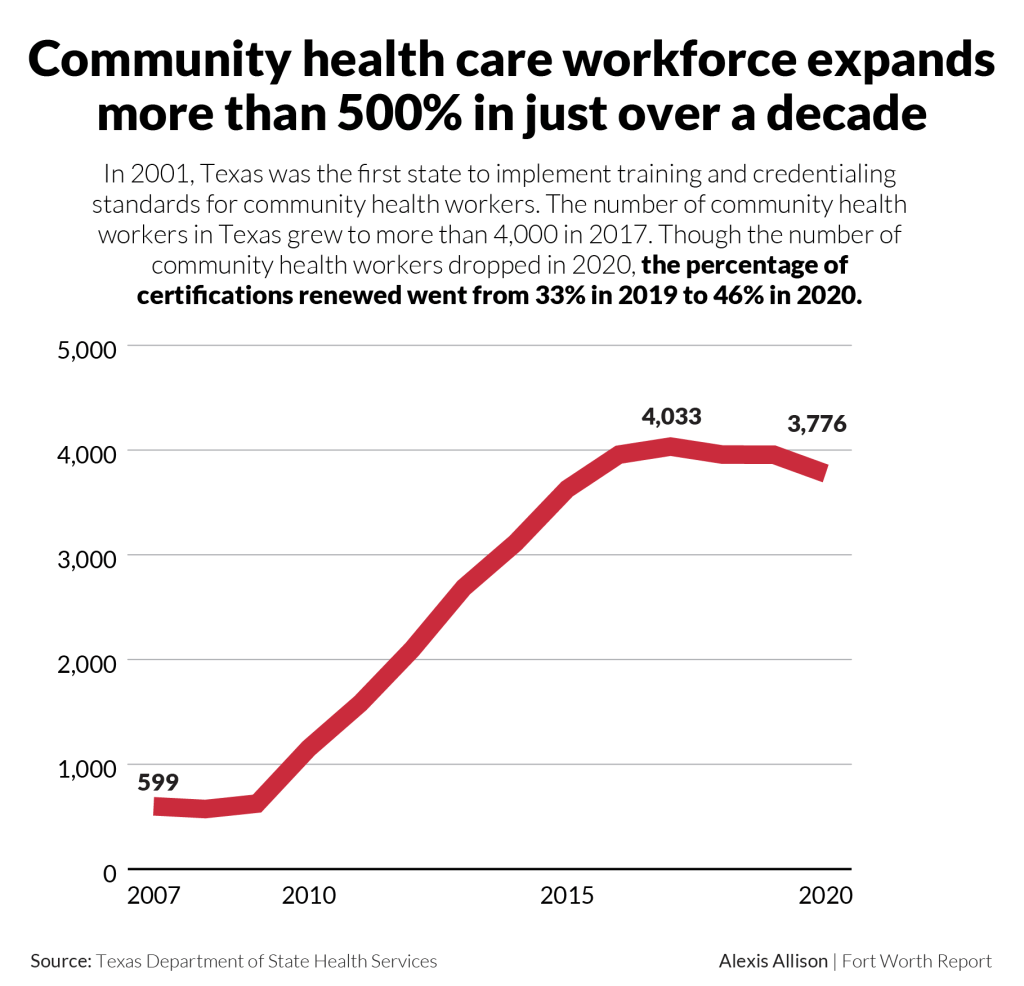

In 2001, Texas was the first state to implement statewide training and credentialing standards for community health workers. In nearly 20 years, the number of community health workers in Texas has grown from fewer than 500 to around 4,000.

“Texas has a really robust and well-oiled system for educating our community health workers,” said Teresa Wagner, a community health worker instructor and an assistant professor at The University of North Texas Health Science Center.

That well-established system, she said, helped public health workers connect with hard-to-reach populations during the pandemic. “They’ve become a huge topic of conversation, especially because of the disparities that we’ve seen with COVID-19,” she said.

For decades, research around the country has addressed the role and efficacy of these health workers in expanding access to care and reducing disparities in their communities.

For example, in Detroit, Black and Hispanic adults with Type 2 diabetes had healthier hemoglobin A1c levels and more self-reported understanding of their disease after working with community health workers than the same group who didn’t, according to a randomized, controlled study about interventions for diabetes care.

When it comes to cancer care, like screenings, diagnostic procedures and wellness exams, people who interacted with community health workers or patient advocates were more likely to get screened and, for those with cancer, receive a definitive diagnosis within one year than those who didn’t. All but two of 24 studies in this systematic literature review reported statistically significant positive outcomes from these interventions.

Like King, Holloway spends her days meeting people in the community: Cataloguing resources, giving presentations, attending health fairs, visiting churches and parks and other local spaces.

She measures her own success in a simple way: if she sees someone join the WIC program after she connects with them in the community.

“Even if it’s one or two people, and they tell me how successful the program was, and their child graduated from the program, that is helpful,” she said.

As insiders who “look and sound like the people we work with,” community health workers help build the trust that can lead to these outcomes, Padilla said in the webinar.

They know how to address specific concerns from a specific community with personal experience — unlike a clinical provider who may not understand the living situation of their patients, Wagner, with The University of North Texas Health Science Center, said.

“Providers sometimes give people instructions, but they have no idea when those people get home, whether they have the money to buy that medication, whether they have transportation to go get that prescription, whether they have food to take the prescription with, whether they have electricity,” she said. “All of these barriers play a role in compliance.”

As a result, she said, a patient who doesn’t follow through with treatment may be labeled “non-compliant.”

“But it really isn’t that they are intentionally not being compliant; it’s that they don’t have the understanding, the culture or the resources to support what it is we’re asking them to do.”

Community health workers not only come from the communities they serve, they’ve often personally experienced the disease they’re trying to address. During the webinar, Padilla called it “lived experience.”

“That opens the door to additional knowledge about resources that are available,” she said. “We’ve been there — a lot of times — and done that.”

Becoming a community health worker in Texas

In 2007, King felt a lump. She was 45, a real estate broker and single mom to two daughters in high school. When her scans confirmed cancer, she waited until Christmas break to tell them.

Over the next year, she went through surgery and chemotherapy, lost her hair, and learned the intricacies of paying for cancer. When her first bill came, it was nearly $40,000, and King had no insurance.

So, she asked about options. She found government insurance for high-risk patients. She found a financial navigator at Moncrief Cancer Institute who helped her get her bills down. And at the end of the day, her surgeon, plastic surgeon and anesthesiologist agreed to provide her care at no cost.

“The moral of my story is to reach out and look for resources,” she said. “There’s people out there, they can’t pay for their medicine. They don’t have insurance. So because they don’t have insurance, they don’t look for resources … You don’t have to have insurance. You just have to open up and ask. Look for it.”

“The moral of my story is to reach out and look for resources,”

– Carlene King, community health worker at Cancer Care Services

During her treatment, a social worker kept telling her about Cancer Care Services, a local nonprofit that provides support to cancer patients, survivors and their caregivers for free. She was uninterested — she figured her income from her real estate work was too high. Then the woman told her about the massages.

“They actually try to figure out how to help you,” King said. And when you walk in, “everybody’s like family.”

Cancer Care Services ended up giving her massages for free — and paying her insurance premiums. She proclaimed their goodness in everyday conversations in the years that followed and, in 2019, they hired her as a community health worker.

King doesn’t usually share her cancer story with people — it’s not about her, she said, and her experience will differ from another person’s. But, she shares the resources she learned along the way. And if it weren’t for her cancer, she wouldn’t be doing the work she’s doing.

Holloway grew up in Liberia in the 1960s. She remembers trailing the women in her community to the local market. She watched how they cared for neighborhood kids, even the children that weren’t their own. It was a “turning point” in her life, she said; before then, she’d wanted to be a nun.

She carried the communal spirit of her childhood — she had “lots of mothers and fathers growing up” — to northern California, where she moved to escape Liberia after the country’s coup in 1980.

As a young woman moving through the U.S. for the first time, she didn’t know how to navigate the health system when she became pregnant. A new friend who happened to be a midwife helped educate her, and that experience of advocacy still informs Holloway’s work.

“One of the things that I do and we do is advocate for people like me who didn’t know anything about the healthcare system and didn’t know anything about health,” she said.

How to become a community health worker in Texas:

In Texas, any resident who’s 16 or older can become a community health worker after completing 160 hours of training in the eight “core competencies,” things like the ability to teach and stay abreast of local resources. People who’ve accumulated at least 1,000 hours of community health work services within the past three years can also be certified based on their experience.

Holloway followed her then-husband to Texas and became a medical assistant. When the time came for her to choose nursing or something else, she knew she wanted to keep tabs on a family’s health after they left the hospital. She became a community health worker in 2011.

Like King, Holloway harnesses her training and her own experiences as an immigrant in a new system to inform her work. Still, she said, it’s never about her.

“I bring my story (to work), but I don’t let their story be my story, because everybody has their own story,” she said. “My story helps me to be able to be a better community health worker. Every day, I’m a work in progress.”

Alexis Allison is the health reporter at the Fort Worth Report. Her position is supported by a grant from Texas Health Resources. Contact her by email or via Twitter. At the Fort Worth Report, news decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

This article first appeared on Fort Worth Report and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.